Alexandra Johnson

In Spring 2018, I had the privilege of working on a cold case as part of a Forensic Psychology course with Dr. Bryanna Fox at the University of South Florida. Collaborating with other students on the case served as the applied half of the course, where we were able to use our newfound knowledge of forensic psychology to offer new perspectives on an unsolved homicide. At the end of the course, we will present our findings to the law enforcement agency we have been working closely with, so they may follow any viable leads.

How do cases become “cold?”

A “cold” case is simply a case that is unsolved, that may not have an investigator assigned to it, and in some agencies is more than a year old or has been inactive for a year or more. The term “cold” was coined by the media in the 1980s after law enforcement agencies began to form units for pending or unsolved cases. “Cold” just sounded more interesting for media and entertainment purposes. This term may imply that a case is not important, is unsolvable, or has been forgotten. However, such cases were investigated and are missing the piece needed to secure a conviction (Walton, 2006). There is little a detective can do if witnesses do not come forward or evidence simply did not exist or was not collected. Additional factors may contribute to a case going cold such as the location of the crime scene, technology and the ability to analyze evidence, and organizational factors like the number of detectives assigned to a case, promotions and transfers, initial reporting, leadership, overall organization, and department budgets (Walton, 2006).

While the term “cold case” may sound negative, the heightened interest in unsolved cases has stimulated public interest in law enforcement procedures, encouraged witnesses to come forward, moved law enforcement agencies to dedicate resources to solve open cases, and serves to remind murderers that their crime is not forgotten, and investigative efforts are still underway (Walton, 2006).

Who are the victims?

Since the 1960s, over 200,000 murders have been left unsolved in the United States. In 2015, the national clearance rate for homicide was roughly 64% (Kaste, 2015). Because there are no statutes of limitations for homicide, most cold cases are victims of murder. However, cold cases may also include missing persons, homeless persons, unidentified victims, accidental deaths, suicides, and unclassified murders (Walton, 2006); meaning the number of unsolved cases is probably much higher than estimated.

What can be done with a cold or unsolved case?

The detectives who pick up cold cases must possess not only exemplary investigative skills, but also be up-to-date with current forensic science and able to think outside of the box. They face additional challenges including “files and reports that are lost, evidence unaccounted for, and what may now appear to have been viable and obvious leads that were not followed up or acted upon (Walton, p.6, 2006).” Kennedy (2015) distinguishes three main components of cold cases: time, technology, and tenacity. While time is usually what has caused a case to go cold, it can also be used as an advantage during a revitalized investigation. Relationships change over time. For better or worse, someone may be willing to share information years later that they were not willing to share during the initial investigation. Also, suspects may become more confident in their crime(s) as time passes and confide in others who originally knew nothing about the case. It is pertinent to look for witnesses that suspects may have told about past crimes. This means tracking down who they worked with, became friends with, lived near, and even dated.

Technology also drastically changes over time. Some advancements include DNA, different light sources, and databases for fingerprints and firearms. When investigating a cold case, one of the first priorities should be to reexamine evidence and utilize the most up-to-date technology. All evidence should be resubmitted. Lastly, Kennedy (2015) discusses tenacity. One of the biggest advantages a cold case has is a new set of eyes, a new perspective. Cold case detectives or squads must employ creative techniques to fill in the gaps. This may mean asking questions that were not asked before and revisiting leads that were not followed the first time.

The first step in reopening a cold case is to review the case file. The case file should include police reports, interview transcripts or notes, DNA results, contact information for all parties involved, and so forth. While becoming familiar with the case, it is important to identify inconsistencies in witness statements, suspect interviews, and case notes. All inconsistencies should be thoroughly examined. If possible, the detective should contact the original investigator, the evidence should be resubmitted, and the current investigators should visit the crime scene. The next substantial step is to conduct interviews with all possible suspects and witnesses (Kennedy, 2015). Once all of these steps are completed, the hope is that new information will lead to the case to being solved.

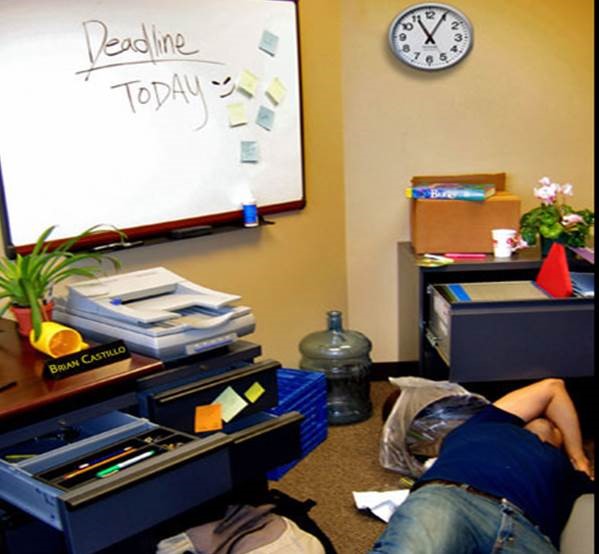

How does it feel to be a student working a cold case?

As a class, we followed the checklists and suggestions listed in empirical research. We began by dissecting the case and becoming familiar with all the suspects, witnesses, and the victim. As the weeks went on, we individually identified inconsistences in witness statements and reports that were important to follow-up with. We visited the location of the crime scene. Although much has changed since the date of the murder, we were able to get a feel for the drive time between various locations and the overall characteristics of the site(s). We spent numerous classes brainstorming and collaborating. The class not only challenged my critical thinking skills, but also my ability to work with others. It can seem silly to create extravagant and seemingly impossible or ridiculous theories as to how the murder happened. But, working to disprove such theories has helped greatly in building a plausible series of events. Working through scenarios provided by different students brought to light new suspects and/or witnesses, new evidence, adjustments in the timeline of the crime, and much more.

Working a cold case has been fun, but extremely difficult at times. Dr. Fox provided us with resources such as detectives, an anthropologist, and numerous other experts that have been paramount to our progress in the case. Without their assistance and guidance, it would have been nearly impossible. We have a good chance at solving the case; but even if we do not, there have been valuable lessons along the way. We have learned what it takes to investigate a homicide, both in terms of critical thinking and tangible resources, how forensic science and law enforcement investigations have advanced tremendously over time, and what kinds of evidence it takes to bring a case to a prosecutor. All these lessons can be taught from a textbook, yes, but only by hands-on experience are students able to feel the excitement when you make a break in a case, or the frustration when you do not have information you want! Overall, it has been a valuable and unforgettable experience that I hope we are able to share more about in the future.

References

Kaste, M. (2015, March 30). Open cases: Why one-third of murders in America go unresolved. Retrieved April 05, 2018, from https://www.npr.org/2015/03/30/395069137/open-cases-why-one-third-of-murders-in-america-go-unresolved

Kennedy, J. (2015). Lessons learned: Cold case homicide checklist. Blueline training group

Walton, R. H. (Ed.). (2006). Cold case homicides: Practical investigative techniques. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.